Mahler - Symphony no. 3 (Review)

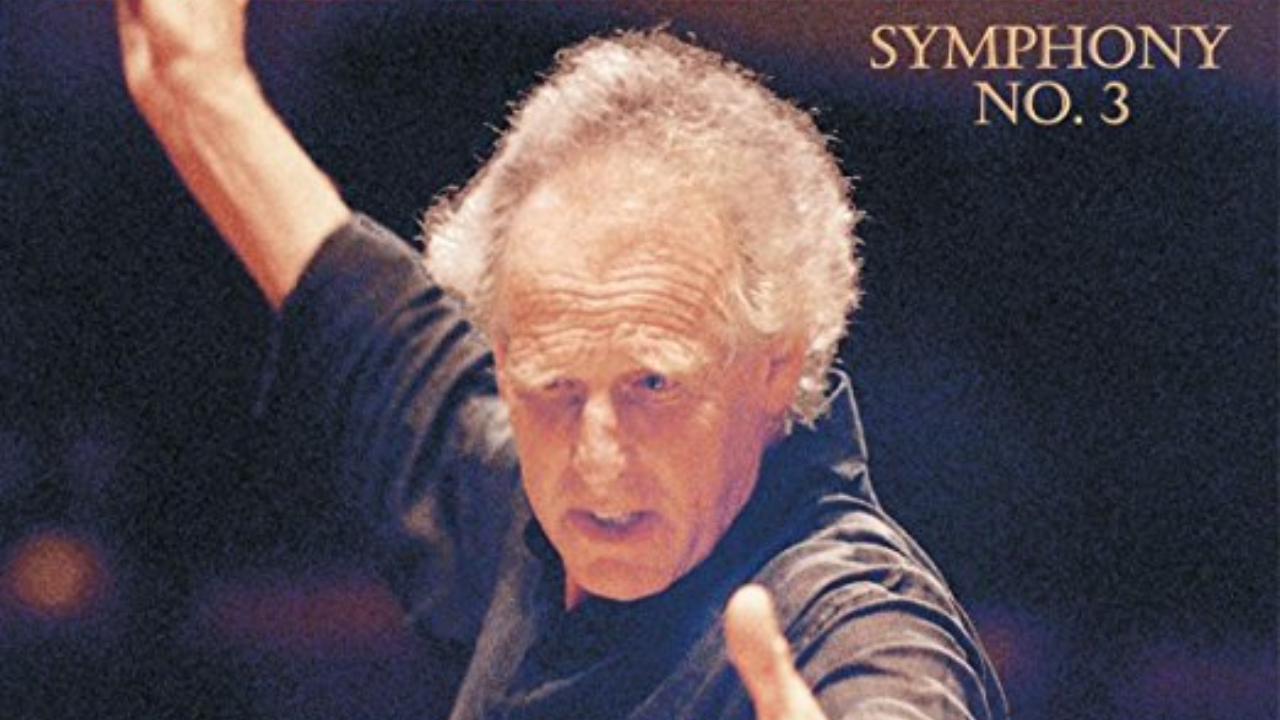

About a year and a half ago, I heard the Mahler Third conducted by Benjamin Zander at Jordan Hall in Boston. After the concert, the conductor was circulating among the milling crowd, as is his wont, greeting friends and students. A young man approached—and was unable to speak. Mr. Zander gave him an encouraging hug. It was that kind of concert. In the immediacy and intimacy of Jordan Hall, this colossus was a visceral experience. Mr. Zander and the Telarc engineers have attempted to duplicate for the home listener the kind of experience we had that night. They have succeeded to a notable degree (I haven’t yet heard the SACD). The recent recording by Michael Tilson Thomas is somewhat more spacious and naturally balanced, while that of Pierre Boulez is more incisive and immediate, while not being as purely impactful. All three are sonically very impressive.

The opening features a ghostly and atmospheric tam-tam. The initial march theme is subdued—the inertia of elemental, frozen winter. Zander’s discussion on the accompanying disc (illuminating and entertaining as always) speaks of the volcanic forces of nature in this first theme, and the undercurrent of rumbling bass drum and charging basses and cellos is the embodiment of those forces. The contrasting second theme is (Zander quoting Mahler) “the mood of brooding summer mid-day heat; no breeze is moving, all life is at a stand-still, the sun-drenched air trembles and flickers. . . .” I had never thought of the two themes as two different scenes, slowly moving closer and then clashing in a cinematic way; but that is what is conveyed here—black and white in Technicolor, as it were. The trombone solo (I auditioned from advance CDs, so I’m assuming it is principal Dudley Bright) is at first especially raucous and unpleasant, as it should be; its later appearances are mournful. The delicately trembling strings of the second theme are both warm and perfectly articulated.

The swaggering of the ever-more confident summer theme is captured in all of its naive glory. The Philharmonia winds are especially impressive, clearly differentiating the variety of expressive sounds they are called upon to produce. This performance, as with few others, is a showcase for the subtle effects that Mahler calls for—one is always aware of the harsh, bold statements, but not as frequently of the contributions of harp, glockenspiel, piccolo, or English horn. The “rabble” section is expertly crafted and clearly delineated, as the various themes clash. The fanfare that announces the recapitulation, with its four cymbals, is commanding. The accompanying sense of dread—are we back here again, after all of the progress we’ve made in the last 25 minutes?—is palpable. And the mournful trombone is once again heard to strong effect. The coda is played hell-for-leather. In the concert hall, this was extremely exhilarating, but I’m not sure that it works as well on this recording, where it verges on the hectic rather than on the powerful.

The first of what Zander calls four “intermezzi” is played for delicacy but not wistfulness—the tempo is flowing and the articulation is precise. Mahler suggested that his flower piece is visited by a brief shower, and that feeling is conveyed by the pelting episodes in triple time. The overall feeling, though, is of a carefree summer’s morning. The wind-playing in the third movement is again very impressive, the birdcalls taking flight effortlessly. The posthorn is incredibly distant—is it only a memory? This may be the most effective realization of Mahler’s intention. The wonderful “horn call” episode near the end of the movement is goose-bump-raisingly effective.

The opening of the fourth movement evokes the misterioso marking perfectly. Lilli Paasikivi has a very beautiful voice unhampered by excessive vibrato or mannerism. Her solo is the equal of Anne Sofie von Otter (with Boulez), my current preference in this movement. The Philharmonia oboist (and later, the English horn) gives a suggestion of glissandos in his solos, but his playing is free of the kind of exaggeration that some listeners have objected to in recordings by Rattle and others. The fifth movement is characterized by an exuberant joy in the singing that is contrasted to the solemn nobility of the preceding movement.

An effective performance of the final Adagio of the Third must find a balance between tempo and feeling, and Zander finds it. His tempo is again a steady, flowing one, but there is no sense of undue haste, and the rubato is intuitive. The playing of the Philharmonia is refined and warm. The final three minutes have a majestic beauty seldom equaled on disc—you get an insight into what the young man I mentioned in the beginning of this review was feeling.

We are fortunate to be experiencing a golden age of the Mahler Third Symphony, beginning with Simon Rattle on EMI and continuing with Michael Tilson Thomas and Pierre Boulez (and many would add the live performance by Claudio Abbado). This new one belongs in that impressive company, and, more important, it is another volume in Benjamin Zander’s journey through the Mahler symphonies.

Click here to listen to the recording.

Christopher Abbot - Fanfare Magazine

Christopher Abbot - Fanfare Magazine