Mahler: Symphony no. 2 'Resurrection' - Boston Globe Review

In March 1979, the late Claudio Abbado led the BSO in a trio of magical performances of Gustav Mahler’s Second Symphony, the “Resurrection.”

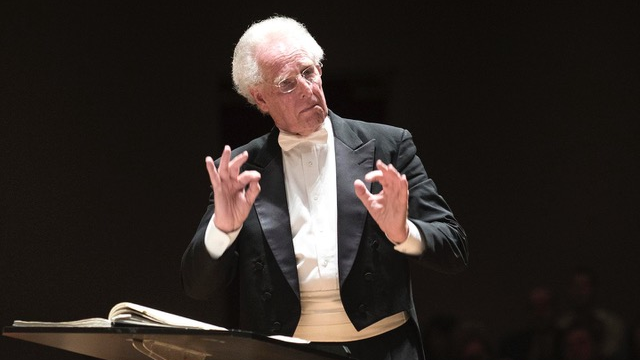

Which was a minor surprise in the wake of his 2012 Linn recording of the “Resurrection” with the Philharmonia of London. Zander there is scrupulously faithful to Mahler’s score, and the interpretation, at 90 minutes, is expansive, but it’s almost too reverent, and the orchestra sounds soft-edged.Friday, the only thing wanting was the texts for the fourth and fifth movements, which for some reason were missing from the printed program. The performance, at 83 minutes, was apocalyptic, with terror and tenderness in equal measure. What needs to rush in this symphony rushed; what needs to be still was still; what needs to be majestic was unbelievably moving. The Philharmonic crackled, with solo playing that was confident and had character; you’d hardly guess this isn’t supposed to be a world-class orchestra. Chorus pro Musica was sufficiently prepared by its director, Jamie Kirsch, that it was able to sing looking at Zander and not at the score.

In the hero’s funeral drama that opens the “Resurrection,” Zander rained down fire and brimstone; death was everywhere. He turned the second movement, a bucolic flashback, into a lilting ländler; here his rubato was more natural than what’s on the Linn recording, and the storm section was more atmospheric. The third movement, which flashes back to the world’s meaningless hustle and bustle, went at a strut rather than the usual sprint; the winds were cheeky, and the Ruthe (a percussion instrument, essentially a bundle of birch twigs) was actually audible.

Jeffrey Gantz - The Boston Globe

Jeffrey Gantz - The Boston Globe